ARPL7011 - 2021

UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND

MASTER OF URBAN DESIGN DEGREE PROGRAMME

Theme: Urban Analysis of Cities in the Global South

By:

Course lecturer: Associate Professor Diaan van der Westhuizen

Contact: diaan.vanderwesthuizen@wits.ac.za

PROJECT DESCRIPTION

The Urban Analysis of Cities in the Global South is intended to develop skills in reading and understanding cities through representations of urban form. The project forms part of the course requirements for History and Theory of Urban Design in the Masters of Urban Design Degree Programme at the School of Architecture and Planning, University of the Witwatersrand. Experts in the field of urban design have developed a range of deductive, comparative, correlational, evidence-based and experiential mapping techniques to capture dimensions of urban reality. Students studied analytical techniques from The Concise Townscape (Cullen, 1960), The Image of the City (Lynch, 1960), History of Urban Form (Morris, 1972), Responsive Environments (Bentley, 1985), Great Street (Jacobs, 1995), The Boulevard Book (Jacobs, 2003), Anatomy of the City (Bachelor, 2002), Understanding City Form and Design (Bosselman, 2008), and Africa Drawn (White, Pienaar & Serfontein, 2015). Through these techniques, time (history), morphology, movement patterns, infrastructure, human and natural features, and other place-making characteristics can be shown graphically. This allows for an understanding of the complexity and systemic nature of the city to be unpacked across various scales.

The activity of graphically analysing urban space and form is an intentional act of selecting, scaling, framing, extracting, superimposition, and drawing. What is not drawn is often more important than the information that finds its way onto a page. This process of critical drawing aims to iterate several dimensions towards a particular framing of a narrative of a city: these dimensions include (1) an understanding of cities, (2) knowing graphic techniques for urban analysis, and (3) applying theoretical ideas through drawing. To understand cities means to synthesise informants and observations in a way to tell a historical, socio-political, cultural, and contextual story of power and place-making that is specific in time and space. To draw the city, is to follow the contours and traces of decision-making, interactions, conflicts, consensus, controlling action and structural interventions over time as physical residues that we call cities. This is done through exploring graphic techniques of figure-ground, networks, morphologies, densities, mix distributions, mental mappings, and experiential structures. Theories in urban design also sharpen our observational skills. These informative texts do not only assist in recognizing patterns of past urban imaginaries, but also help unpack the complexities of the city as a time-based process (to reference Ali Madanipour’ piece entitled Ambiguities of Urban Design) (Madanipour, 1997).

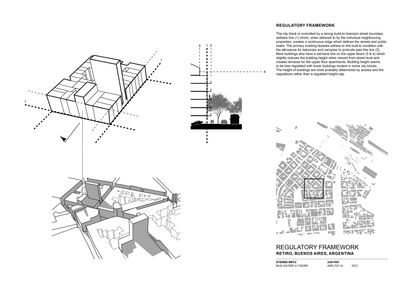

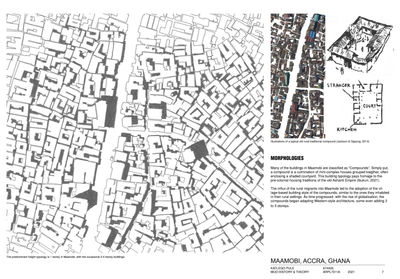

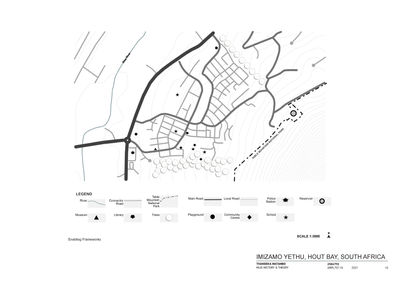

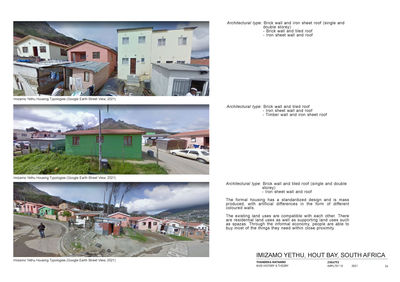

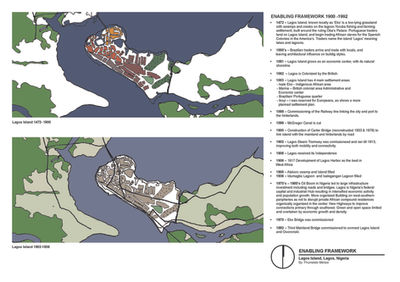

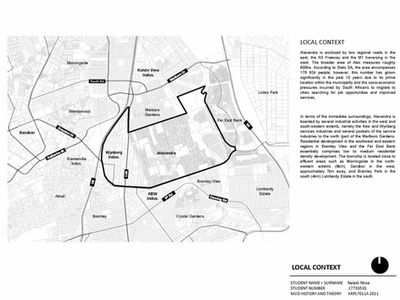

In 2021, students in the History and Theory of Urban Design course embarked on a graphic analysis of a selected case study city in the Global South. The educational challenges of lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic challenged the students to base their research primarily on desktop studies and available cartographic material. The project started with their selection of a city of interest from google maps, arguing issues to be introduced through three initial scales: Block = 1 hectare or 0.01 km² (100mx100m) at 1:500, District = 25 hectares or 0.25 km² (500mx500m) at 1:2500, and City = 600 hectares or 6 km² (2.5x2.5km) at 1:12 500. Thereafter, the students accumulated components of the project through submissions that responded to the weekly themes: (1) Adaptability and Enabling Frameworks, (2) Networks, Hierarchies, and City Grids, (3) Accessibility (4) Transportation Models, (5) Planned Development Models, (6) Urban Form and Density, (7) Urban Mix and Variety, (8) Urban Morphology and Typologies, (9) Legibility, (10) The Public Realm and Human Centred Design, and (11) Regulatory Frameworks: Design Controls, Guidelines and Role Players.

The goal of the 2021 History and Theory of Urban Design course was to offer students an opportunity to read and discuss theories in urban design, broaden their own graphic lexicon, and apply these skills to real-world case studies. Through this engagement, they get a glimpse of the complexities of city building by engaging with histories and theories of urban form and morphology. They also start to see how urban systems are interrelated and how these systems link to human actions, perceptions, behaviour, and use.

References:

Bosselman, P. (2008). Urban Transformation: Understanding city form and design. Island Press.

Bently, I. (1985). Responsive Environments: a manual for designers. London: Architectural Press.

Cullen, G. (1971). The Concise Townscape. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company

Jacobs, A.B., Macdonald, E., & Rofé, Y. (2002). The Boulevard Book: History, evolution, design of multiways boulevards. MIT Press.

Jacobs, A.B. (1993). Great Streets. MIT Press.

Lynch, K. (1960). The Image of the City. MIT Press

Madanipour, A. (1997). Ambiguities of Urban Design. In Town Planning Review, 363-383.

Morris, A.E.J. (1972). History of Urban Form: Before the Industrial Revolutions. John Wiley & Sons.

White, G., Pienaar, M., & B. Serfontein. (2015). Africa Drawn: One hundred cities. Dom Publishers.